[Jeonju International Film Festival] - Borderless Storyteller

Published April 28th, 2022 - Source

Introduction and Interview by Seongkyung Moon

Gina Kim is a filmmaker whose career moves fluidly between Korea and Hollywood. Beginning her artistic journey in visual art, Kim has boldly ventured into a wide range of genres—experimental film, documentary, narrative cinema, and most recently, virtual reality (VR)—with each new work marking a successful foray into uncharted terrain.

Kim studied fine art in Korea and filmmaking in the United States. During her academic years, she produced several experimental video works. Her first feature-length documentary, Gina Kim’s Video Diary (2002), garnered international attention when it was invited to the Berlin International Film Festival. Her narrative feature debut, Invisible Light (2003), was selected for the “Filmmakers of the Present” competition at the Locarno Film Festival and was named one of the top ten films of 2003 by Film Comment magazine. Her 2007 feature Never Forever, the first Korean-American co-production and the first Korean film to enter the U.S. Dramatic Competition at Sundance, is widely regarded as a landmark in transnational filmmaking. Her documentary Faces of Seoul (2009) was screened at the 66th Venice International Film Festival, where she also served as a juror—the first Korean female director to do so at one of the world’s top three film festivals.

Kim’s trailblazing path extends beyond her creative work. She was the first Asian woman to teach in Harvard University's Department of Visual and Environmental Studies, where she also introduced and taught the first Korean Cinema course ever offered by an Ivy League university in the United States. She is currently a professor at the Department of Film, TV and Digital Media at UCLA and was named one of the top educators in global film schools by Variety in 2018.

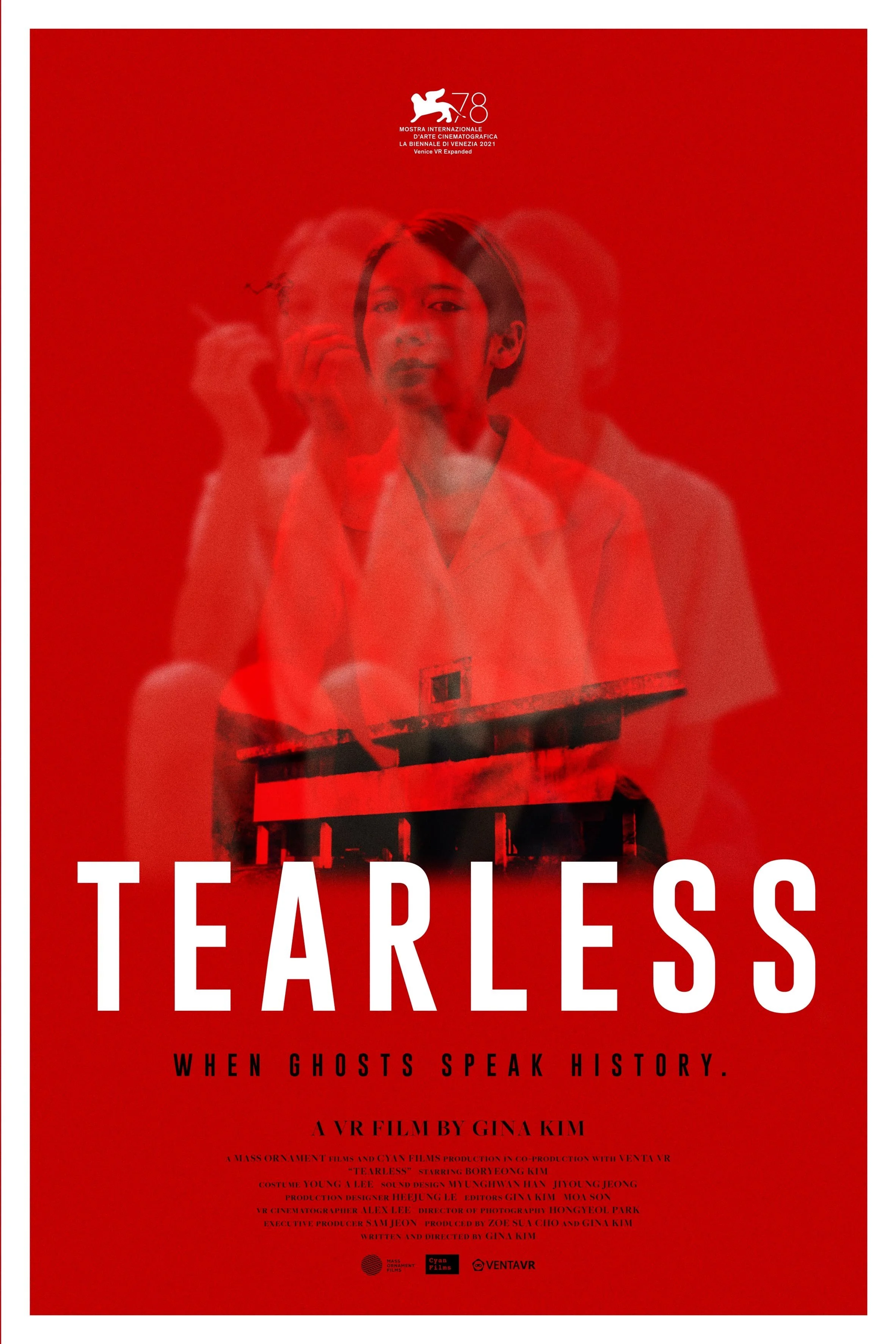

Over the past five years, Kim has released two VR projects that continue to garner acclaim through global venues and awards. Bloodless (2017) revisits the tragic 1992 death of a woman in a U.S. military camp town in Dongducheon, Korea, reimagining the visual and historical narrative surrounding the incident. Tearless (2021) transports viewers to the entrance of a detention center at Soyosan, colloquially known as “Monkey House,” where women working in U.S. military camptowns were confined by the Korean government in the 1960s under the guise of medical treatment for sexually transmitted diseases.

Bloodless was awarded Best VR Story at the Venice International Film Festival at a time when the convergence of VR technology and storytelling was still in its infancy. Through her work, Kim has convincingly demonstrated the cinematic potential of emerging media—not by fetishizing the technology itself, but by anchoring it in the power of story.

Gina Kim is a rare figure in contemporary cinema: a creator of new precedents, a cross-cultural thinker, and a visionary whose work continues to expand the very boundaries of Korean cinema. Her voice stands as a testament to the creative and intellectual possibilities that lie at the intersection of technology, narrative, and lived history.

The Art of Absence: Beyond the Frame, Toward Possibility

Your body of work spans a wide range of moving image formats—from media art and documentary to narrative cinema. Were you ever apprehensive about beginning work in a new medium like VR?

I wasn’t afraid of working in a new medium. I’ve always believed that as long as I can clearly communicate my vision, I can trust the experts around me to guide me through what I don’t yet know. That mindset comes not only from having explored a variety of mediums in the past, but also from my experience working on large-scale commercial films. When you're making a commercial feature, the director’s role—paradoxically—can become quite minimal. The bigger the budget, the more professionals you bring on board, and the more exposed the director’s limitations become. It’s a curious irony: cinema, as a medium, reveals how closely art and industry are entwined.

I’ve directed the first Korean-American co-production (Never Forever, 2007), and I’ve shot commercial films in countries like Thailand and China, where I didn’t speak the language. Final Recipe (2014), for instance, involved a considerable budget and an international crew. Those experiences helped diminish my fears of the unknown, or of new technologies that lie beyond my control.

What do you consider the most fundamental difference between VR and traditional film media?

While there is clearly some overlap between VR and traditional 2D cinema, I resist reducing all forms of VR or immersive media to a subgenre of film. That perspective becomes especially limiting now, as non-narrative, game-engine-based VR works—many of which suspend linear time altogether—become increasingly dominant.

Even in narrative-based cinematic VR, the differences with 2D film are striking, especially when considered semiotically. Traditional cinematic language relies on capturing a single spatiotemporal event from multiple angles and shot sizes, which are then recomposed through editing—a grammar unique to film. But that kind of montage is impossible in VR.

The more fundamental difference, however, lies in the absence of the frame. The rectangular frame of a conventional screen—within which the director controls the world captured through the lens—is an immense form of power. The moment a frame is chosen, everything outside it is excluded. In VR, that frame disappears. Just like in real life, viewers inhabit an open 360-degree space, free to choose where they look. Of course, cinematic VR still employs strategies—movement, sound, and so on—to gently guide the viewer’s gaze. But unlike in flat cinema, we cannot impose a tightly controlled visual field that selects only the butterfly delicately perched on a flower; in VR, the viewer may see the pile of trash where that flower is discarded, the smoky ridgeline in the distance, and the ominous sky above.

From a semiotic standpoint, VR is a far more democratic medium. It relinquishes visual control to the audience, allowing for a multiplicity of perspectives and experiences.

Your first VR work, Bloodless, addresses the 1992 murder of a sex worker in Dongducheon camp town. What led you to explore this case through VR?

The “Yun Geum-i Incident” happened during my first year of university. I vividly remember the shock I felt when I first read about it on a campus bulletin board. We all had an uneasy awareness that women working in U.S. military camptowns were vulnerable to all manner of violence—but it was the first time a specific case had erupted so forcefully into the mainstream public consciousness. We were outraged, we marched, we protested.

But what disturbed me most wasn’t just the brutality of the act—it was the widespread circulation of the victim’s image. Yun Geum-i’s mutilated body appeared in pamphlets, posters, and newspapers. Her death was used to galvanize political action, but at the expense of her dignity. I felt a visceral, instinctive anger at how a woman’s image could be endlessly reproduced, weaponized for a cause, and stripped of humanity. At the time, I had no language or medium with which to express that anger. What I felt eventually settled into a sense of unresolved debt—an internalized guilt toward the victim herself, whose rights and personhood were erased in the name of activism.

In many ways, that experience shaped my identity as an artist. The visual rhetoric of that incident—grainy black-and-white photos, sensationalist slogans, poorly translated English phrases—marked me deeply, like a scar. It awakened in me a critical awareness of what it meant to be a woman in a postcolonial society. I never forgot the urge to someday express this story through film.

Over the years, I wrote scripts and discussed the project with both Korean and international production companies. But I couldn’t find an ethically responsible way to tell it within the constraints of narrative cinema. Production companies wanted a genre thriller with male leads—a detective and a killer—while the woman remained a silent victim, reduced to a corpse. I, on the other hand, wanted to center her experience without reproducing violence or exploiting her image. There was no middle ground.

Then I encountered VR. What struck me was that this medium wasn’t rooted in voyeurism, like traditional film, but in experience. In VR, the viewer doesn’t merely watch—they enter the space, becoming part of the environment being represented. That presence—being with rather than looking at—suggested to me the possibility of a paradoxical approach: to speak of violence without visually reenacting it.

What was the most important aspect for you in the making of Bloodless?

The first aesthetic motif that flashed in my mind—like a light bulb turning on—was “the absence of the body.” I wanted to reconstruct the event’s time, space, and circumstances not through the victim’s body, but through its absence. I think I wanted to reverse the process by which that horrific image—the one I saw in a crime scene photo 25 years ago, which was later endlessly reproduced online—had spread. I wanted to delete that image. So at first, I planned to recreate the crime scene in VR—not with the body present, but as an empty room where violence had occurred.

I scoured everything I could find in the U.S.—articles, papers, books, even internal military publications—but no source revealed the details of the room itself. The materials I found in Korea weren’t much better. I even contacted journalists and authors who had described the scene at the time, only to discover that they’d reproduced it based on photos, not first-hand experience. The building where the room had once been still stood, but the interior had been remodeled beyond recognition. That’s when I realized the narrative structure I had originally envisioned wouldn’t be possible.

Another unexpected factor emerged in the process. When I began research, I didn’t think I’d be able to find traces of the 1992 military camptown where the victim had lived. Twenty-five years is enough time to erase everything in a city near Seoul, I thought. But once I began investigating, the reality turned out to be something else entirely. The Dongducheon camptown had been preserved as though pickled in formaldehyde—frozen in time. The Crown Club, where Yoon Geum-i had met the U.S. soldier that night, had ceased operations but still looked exactly the same. There were boutiques with a 1960s vibe, corner stores filled with Spam and Pringles—places untouched by Korea’s frenzy of urban development. At night, U.S. and Korean soldiers patrolled the streets with machine guns, while ’90s music played from clubs still frequented by groups of American soldiers. The entire atmosphere was disorienting—these were sights unimaginable in 2016 Korea, yet they were right in front of me.

After multiple visits to the same area—and experiencing a few dangerous situations—I came to feel that documenting the present-day landscape of the Dongducheon camptown was just as important as telling the story of Yoon Geum-i’s case. That realization led me to restructure the project: capturing the camptown as it stood in 2016, while poetically reconstructing the events of 1992.

Did your experience with Bloodless influence your approach to Tearless in any way?

What I learned from Bloodless was that images captured in 3D 360° are incredibly effective for archiving spaces—because they offer a truly immersive experience. So for Tearless, one of the primary goals became documenting the site of the Soyo Mountain Detention Center in immersive media, alongside telling the story of the women who were detained and subjected to forced treatment there.

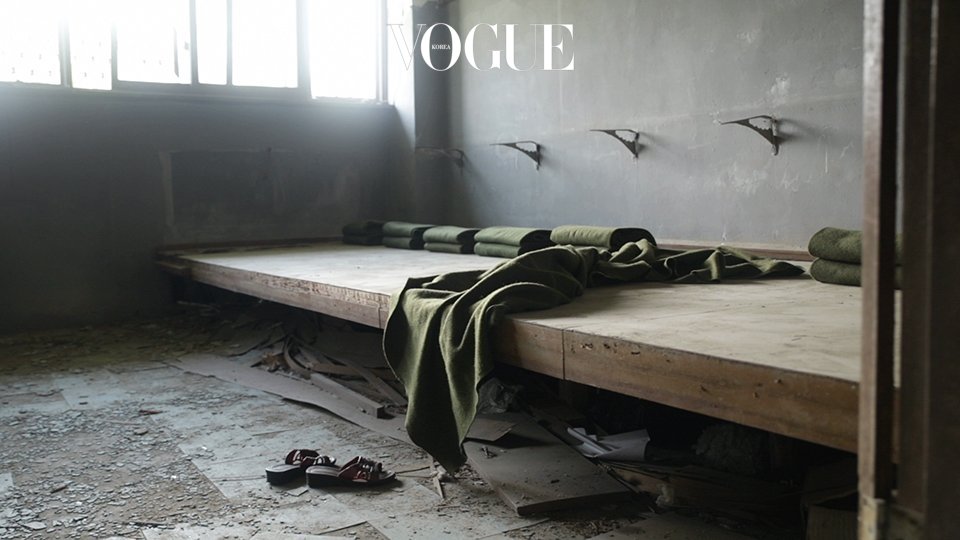

The Soyo Mountain Detention Center often comes up whenever the issue of U.S. military comfort women is mentioned, so it was one of the first places I visited while scouting for Bloodless. When I first stood in front of the building, what I felt was a chill. Not the kind of chill that comes from something old or decrepit, but a visceral recognition that something terrible had happened there. The interior was filled with so much garbage that it was hard to move around. It had been used as a shelter for the homeless, a party space for aimless teenagers, a filming location for YouTubers—the traces of which had all rotted into refuse. The building was in a serious state of disrepair. After the record-breaking monsoon of 2020, I began to wonder how much longer it could even stand.

In the summer of 2021, even though the COVID-19 pandemic made production incredibly difficult, I decided to push forward. With doorframes and windows disappearing by the day and graffiti sprouting on the walls like mushrooms after rain, we couldn't afford to wait any longer.

What’s the difference between narrative construction in VR versus in film? How did you build the narrative structure in Bloodless and Tearless, and how did you determine where they begin and end?

The key difference is in the power dynamics between director and audience. In 2D cinema, the director has total control: everything outside the frame can be excluded, and editing determines exactly what the audience sees, feels, and when. But in 360° immersive media, that control is no longer possible. Some filmmakers dislike this, but I found it revolutionary.

Fortunately, I had experience directing experimental theater, so I was already familiar with formats where the audience (in this case, the VR camera) sits at the center while actors emerge from all directions—front, back, sides—to drive the narrative forward. That said, I didn’t want to give up cinema’s unique relationship with time. So I ended up using a narrative structure similar to that of my grad school mentor, James Benning, whose landscape cinema advances story through shifts in space rather than cuts within a scene.

In Bloodless, the narrative was structured around the victim’s movements and the subtle transformations of those spaces. The night she was killed, Yoon Geum-i met the soldier at the Crown Club, and he followed her back to her room—her home and workplace—where the murder occurred. The camptown isn’t that big, so there weren’t many possible routes between those two places. Together with my line producer and assistant director, we walked the camptown’s alleys over and over again, exploring and debating the route. Ultimately, the narrative was constructed through roughly twelve spaces, beginning at the wide, open entrance to the camptown and gradually narrowing into alleyways, ending in the room where Yoon Geum-i was killed.

Tearless required a different approach. The focus wasn’t on one specific woman, but on many women who had been confined in that building. Instead of spatial movement, the structure was built around temporal progression—based on a daily schedule posted on the detention center wall. Written in elegant, old-fashioned script, it listed each hour’s activities: 7 AM wake-up, 7–8 cleaning and washing, 8–9 breakfast, 10–11 treatment, 11–12 venereal disease education, 3–5 PM inspections and further treatment. Reconstructing a single day inside that building, based on that schedule, became the foundation of the film’s narrative.

Can you describe a moment when the VR medium either collided with or fused seamlessly into the storytelling?

Overcoming the psychological distance between screen and viewer is never easy in conventional 2D cinema. Yet in VR, that psychological gap diminishes dramatically—sometimes vanishing altogether. This is because the psychological mechanism of VR is not voyeurism, but experience. In a traditional theater, a bomb might explode on screen, blood may flow freely, and yet the audience continues eating popcorn. But in an immersive VR film, the reaction is wholly different. Even when fully aware that the experience is virtual, viewers often feel fear, physically recoil, or have the instinct to flee.

While developing Bloodless, this property of the medium came into sharp focus and became the flesh layered over the narrative skeleton of Yoon Geum-i’s final movements. After being struck by her assailant, Yoon bled slowly to death over the course of two agonizing hours. I began to reflect on the extremity of loneliness she must have endured in that small room during the last conscious moments of her life. What emerged was an image of her spirit—caught between life and death—rising from the floor to return to the streets where she had once sought customers night after night.

She becomes a kind of revenant, drifting through the streets in search of someone willing to listen to the story of a life cut short before it had truly begun. That listener is the viewer of Bloodless. Neither perpetrator nor victim, the viewer enters the camptown as an innocent bystander. And gradually, they begin to notice the presence of a woman—beautiful, enigmatic—hovering at the edge of their gaze. Inevitably, she eludes them, until they are compelled to seek her out.

Then, in the narrow passage of an alleyway, the viewer encounters her directly. But instead of relief, the moment is overwhelming. She continues walking toward them, eventually passing through their body. Only then does she turn to face them and meet their gaze. That moment—when viewer and woman, now joined, lock eyes—is a moment of transfiguration. She draws them back into the space and time of 1992, into the room where she was killed. It is a moment of sacred collapse between past and present, subject and witness.

If cinema builds a frame through which the director unfolds their vision, VR constructs an entire world and places the viewer inside it. In that case, who is the storyteller in VR?

To build a world and then set the viewer loose within it—yes, that's beautifully and precisely put. Within such a construct, the storyteller becomes the relationship itself: the interaction between main character and viewer. How that relationship is defined may differ from work to work, but the principle remains.

So who is the storyteller in Bloodless and Tearless?

In both, the storyteller takes the form of a spectral figure—a woman who exists fully within the world of the film, yet remains elusive to the viewer. One might call her a ghost. In Bloodless, a woman symbolizing Yoon Geum-i wanders the streets like an apparition, playing a kind of hide-and-seek with the viewer. She does not immediately command attention; at first, she appears no different from any other passerby. But gradually, she begins to orchestrate the viewer’s awareness, guiding them to hear her story.

If the viewer fails to notice her, or fails to follow her cues, the narrative collapses. She is both story and storyteller. And in that sense, storytelling in VR is no longer something projected toward a passive audience—it is an act that requires participation, attention, and above all, presence.

In Tearless, too, a young woman emerges—an embodiment of those who were once incarcerated in the medical prison for camp town sex workers. Before revealing her pallid, emaciated form to the viewer, her presence is first made known only by the delicate sound of water. Each time a droplet falls—each time she appears—the landscape of the Soyo Mountain medical prison begins to transform, and the viewer is drawn into a shared experience of the time she endured.

Where once stood an empty bedroom, military blankets begin to appear, folded in parallel lines. In another moment, a gynecological examination table materializes in an abandoned room, just beyond the green shimmer of leaves swaying through a shattered windowpane. Initially guiding the viewer only through sound, she eventually manifests before them, her eyes beckoning them to follow. Should the viewer fail to notice her or heed her silent cues, the meaning and interconnection of the surrounding space and time will remain elusive.

In this work, storytelling is not something the viewer passively receives. It emerges only between the viewer and the woman—formed through a reciprocal relationship that must be actively constructed.

What kind of experience did you hope viewers would have while watching Bloodless and Tearless? And how did audiences actually respond?

I hoped that the subject of U.S. military comfort women—so often approached as a burdensome historical issue—could instead be felt through the senses, rather than absorbed through intellectual or informational frameworks. I wanted to speak to the stolen human rights of these women in a way that sidestepped ideological entanglements and allowed for a visceral understanding—something no one could deny.

Despite initial doubts—after all, could a low-budget VR work convey such a weighty historical trauma?—I hoped that even those unfamiliar with the context could feel the pain of these women through their skin, their ears, their hearts. And I am deeply grateful that many viewers did.

Though the works are minimal and elliptical, viewers unfamiliar with the history of U.S. military comfort women expressed a profound sense of shock. This was especially true for international audiences—some of whom didn’t even know that U.S. forces are still stationed in South Korea. Museums and festivals, aware of the sensitivity and gravity of the subject, often organized special programming around the screenings. One that remains vivid in my memory was at the Eye Film Museum in Amsterdam, where the screening was accompanied by a panel on the history of the U.S. military presence in Korea and its cinematic representations.

Through screenings at international film festivals and art museums, I was able to share the work with audiences from across the globe—and in doing so, came upon something striking. Reactions to the films differed dramatically based on gender, race, and nationality. In Bloodless, some viewers experienced profound fear simply by being present in the camptown—not watching it, but inhabiting it. The intensity of this fear was greatest among Asian women (particularly Koreans) and least among white men.

For example, many Korean women shared that they began to feel overwhelming fear from the moment night fell in the camptown. By contrast, most white male viewers reported sadness as their dominant emotional response, rarely fear. Among Asian women, those from countries with histories of colonial occupation exhibited a more intense fear response than those without such histories. It was sobering—and painful—to witness how sharply these emotional responses tracked with the power dynamics of a postcolonial, imperial, capitalist world.

Could you speak about your relationship with images and cinema? How has your background in fine art shaped your creative journey into filmmaking?

What I gained from studying fine art was, above all, a fluency in visual language—an ability to both read and write with images. The discipline of observing, analyzing, and transforming high-quality imagery into one's own visual vocabulary was a deeply formative part of my education. At the time, we were also rigorously trained in aesthetics and art history—so much so, in fact, that there was an almost punishing emphasis on memorization. (laughs) In just one course on East Asian art history, for instance, we were expected to memorize thousands of slides. A typical exam would show a small, magnified detail of one painting, and we were required to identify the period and justify our answer.

In truth, it wasn’t merely about memorization. The exercise demanded an acute awareness of the artist’s bodily gesture embedded in each brushstroke, the nuanced modulation of ink tones, and how these qualities inevitably embodied the spirit of a given era. One came to recognize not just the artist's hand, but the time through which it moved. In retrospect, every class felt like a lesson in the sociology of art.

It was with this foundation that I first encountered video art during my senior year of college. Naturally, I was attuned to the unique properties of the medium and the new aesthetic possibilities it suggested. Unlike a painting, which exists as a singular and irreplicable tableau in a gallery, video is fundamentally an art form of the age of mass reproduction. That realization captivated me.

While it's common today to shoot a moving image on an iPhone, at the time, video was not yet a truly democratized medium—but you could just begin to sense the early signs. Even so, it was clear that with this new technology—video—cinema was poised for an explosive transformation in the 21st century. Unlike film cameras, which required specialized equipment, personnel, and capital, the lightweight and accessible video camera offered a radically new kind of freedom.

From that point on, I began immersing myself in the works of early video artists and media activists from the 1960s and ’70s. That encounter marked the beginning of my journey into cinema.

With the proliferation of social media and evolving media technologies, public expressions of private life have become commonplace. In light of this shift, how do you now regard Gina Kim’s Video Diary, two decades after its completion?

Since its completion in 2002, Gina Kim’s Video Diary has been labeled in various ways: a feminist personal documentary, a coming-of-age film, performance-based video art, or even a prophetic experiment that anticipated the age of social media. But from where I stand today—twenty years on—I see it, more than anything, as a kind of gender barometer of Korean society at the time it was filmed.

The late 1990s and early 2000s marked a phase of masculinization and industrialization in Korean cinema. 1997 saw the simultaneous debut of a cohort of prominent male directors who would go on to define a new era. The film Shiri, released in 1999, symbolically opened the floodgates of a burgeoning film industry. Yet in this narrative of growth, women were absent. The deepening gender divide in contemporary South Korea—described by some as a “gender war” of the 21st century—was, in retrospect, already foreshadowed by the exclusion of female voices from cinema during this period.

It is in this context—when postcolonial Korean society was striving to reclaim masculinity, casting off its feminized status as a former colony—that Gina Kim’s Video Diary was both shot and edited. That alone renders the work highly charged with meaning. At the time, I was studying film in a U.S. graduate program, immersed in an art education steeped in Eurocentric discourse. Simultaneously, the cultural resurgence in my home country was unfolding largely through the male gaze. For my coursework, I made European-style modernist experimental films. But as soon as I returned home, I would breathe heavily—almost gasping—and switch on the camera to shoot my video diary.

I was embarrassed by this compulsion, unable to explain why I felt so driven, so obsessively compelled to record the minutiae of daily life. Only recently did I come across some notes from that period. Rereading them now, I see it clearly: I was struggling to articulate the pain of existing as a woman in a postcolonial society. One note read: “I don’t know what I’m doing right now, but someday, someone in the future will be able to explain what it means.” I had an intuitive sense that this anguish wasn’t mine alone. So I documented it—preserved it like a time capsule, hoping that it would acquire meaning later. And in the end, it did. I eventually opened that time capsule, edited the footage, and watched as critics and theorists interpreted its significance. In some sense, the prediction came true.

For this reason, I see Gina Kim’s Video Diary as fundamentally different from the personal videos now widely shared on social media. Certainly, there are points of overlap: narcissism, for instance, as a force that propels the search for identity; the camera lens functioning both as a window to the world and a prison that confines the self. But Video Diary was never created for instantaneous consumption or display. It is not governed by feedback loops or tailored for the viewer. That difference—freedom from the gaze of the consumer—may in fact be a crucial distinction, perhaps even a deeply essential one.

Over the years, you’ve explored the female body and desire through various media. If you believe that a certain story calls for a specific medium, could you reflect on how this alignment manifested in your own work?

Gina Kim’s Video Diary, as the title suggests, is a video diary—one that could not have existed without the medium of video. The other short works I produced during that time similarly relied on analog technologies now nearly extinct—I shot with a VHS-C camera, connecting it directly to a monitor to film myself while simultaneously observing, or surveilling, myself. It was a closed-circuit system where the subject and object collapsed into one: I was the one watching, directing, and filming myself. In retrospect, these works were deeply in conversation with the strategies of feminist artists working under the credo “the personal is political,” and aligned with Rosalind Krauss’s writings on narcissism as a psychological mechanism underpinning the aesthetics of video art.

The process of making Invisible Light (Geu Jip Ap) was quite different. Though the film retained an extremely minimal style, its production demanded the traditional machinery of narrative cinema. I had to abandon the isolated, closed-circuit approach and take the camera out into the world. It required a professional crew and a budget of a completely different order—this, in turn, provoked a shift in medium. Although the film was shot on HDcam to cut costs, it was ultimately transferred to 35mm print for theatrical release. (This was during a moment when digital video had advanced so rapidly that people were declaring, “Celluloid is dead.” And yet, for theatrical distribution, film prints were still necessary!) That moment of transition—between video and film—coincided with my own evolution as a filmmaker. I was trying to bridge the gap between nonfiction and fiction, experimental and conventional cinema, to speak of women’s desires in a more accessible cinematic language. And that alignment, I believe, was no accident.

Later, with Never Forever, I stepped into the world of commercial cinema and embraced a more classical narrative structure. It was my first commercial feature, and I approached it with the intention of subverting the conventions embedded in genre and medium. I wanted to challenge the fatalistic trajectory of 1960s Korean melodramas, where women with desire are invariably punished. I also set out to confront the desexualized portrayals of Asian men in Hollywood cinema—and, most crucially, to disrupt the long-standing cinematic taboo against depicting physical intimacy between white women and Asian men. (Up until then, the only examples within the mainstream cinematic tradition were Alain Resnais’s Hiroshima Mon Amour and Jean-Jacques Annaud’s The Lover.) My response to these deeply entrenched traditions was a direct, formal one: I chose to shoot on 35mm film.

Though not centered on the female body or desire, Faces of Seoul also exemplifies a work rooted in media-specific inquiry. Once image storage on hard drives became stable and the era of fully digital video arrived, one of the first things I did was begin collecting and archiving footage I had sporadically shot of Seoul between 1995 and 2007. These fragments—recorded across shifting media platforms including VHS-C tapes, 6mm tapes, and stills from digital cameras—spanned a decade of technological change. Faces of Seoul was the result: an essay film edited together from this heterogeneous material. Its narration was later published by a French press as a photo-essay book in three languages—Korean, French, and English. At the time, I had no particular expectations for the print version, but when I received a copy, I was genuinely surprised. Embedded within its pages was a QR code that linked to the film’s soundtrack, giving rise to a hybrid media object—neither film nor book, but something entirely new and aural in form.

While VR work carries its own significance in removing the traditional frame, how do you position the gaze of the camera when addressing delicate subjects such as the Yoon Geum-i case or locations like Soyo Mountain medical prison?

I make films with my body. It’s no coincidence that the retrospective currently being organized by Duke University is titled The Embodied Cinema of Gina Kim. If I were to describe the camera’s gaze, I’d say I determine its placement based on the intuition my body provides. Many critics have commented on the camera height in the final room scene of Bloodless. That vaguely suspended perspective—neither high nor low—has led many viewers to say they felt as though they were floating in the space, detached from this world.

Tearless works similarly: the height of the camera subtly shifts depending on whether the scene takes place in the stairwell, the rooftop, or the bedroom. I suppose one could theoretically dissect these choices, but the truth is, they aren’t calculated decisions. They’re made in the moment, driven by intuition—when it just feels right, that’s where I place the camera and frame the shot.

This applies to my narrative films as well. In Invisible Light, there’s a six-minute long take where the female protagonist is engaged in an act of self-pleasure. The shot is an extremely tight close-up—so close it almost caresses her face. In Never Forever, the camera placement during the intimate scenes continuously shifts, responding to the emotions exchanged between the characters and the evolving dynamics of their relationship.

Saying all this now, I wonder—perhaps in those moments of deciding the camera’s gaze, I unconsciously think of the subject as my own body. Maybe this instinctive approach originated from my very first work, Gina Kim’s Video Diary. For me, filming something with a camera is an act of preservation—symbolically, it’s an act of embrace. It’s about holding onto something I wish to protect from erasure, to cradle against the forgetting that time imposes. It’s an act grounded in respect and affection for the subject. If I may risk saying something a little bold: as someone with a body capable of generating life, perhaps all the subjects I film are, in some way, me. You could call this an excess of empathy—but regardless, it’s certainly a stance that differs from exploiting or objectifying the subject.

The ethics of representation is a deeply complex issue. Have you faced any dilemmas in this regard, or made particular efforts to navigate them?

In good art, form and content are inseparable. Just because a certain aesthetic strategy worked well with a particular subject in one project doesn’t mean you can reuse that same formula and automatically expect another successful work. In powerful work of art, the relationship between form and content is never fossilized—it isn’t something you can standardize. It’s a living, breathing force. The moment you begin applying a method like a universal cure-all, thinking “Ah, this is the right way,” is when art starts to decay.

That’s precisely why speaking in general terms about the ethics of representation is dangerous. There are many well-meaning principles—like “Don’t exploit the subject’s image,” or “Don’t force empathy on the audience”—but those remain just that: principles. When you try to apply them to actual, nuanced situations, things become far more complex than you could have imagined. Every person, place, and event encountered in the process of filmmaking is uniquely individual. And the dilemmas that arise in trying to capture those within a cinematic medium are likewise unique. You have to establish a new ethical relationship each time, depending on the subject matter, the subjects themselves, and the medium you’re using. Refusing to fall back on generalized ethical formulas—that, I think, can actually be the first step. Creative work is an ever-changing, living process. So finding answers with difficulty is the only real answer. Ethical knots deserve to be untangled slowly and with care.

That’s why sometimes, it’s equally important to let go a little. I’m not the only one striving to do meaningful work. And while I do my best from where I stand, I also try to stay aware of how small my efforts are in the grand scheme of things. Holding onto the knowledge that my way isn’t the only way—that I might even be wrong—has helped me move forward in my work.

What is the significance of addressing a story from 30 years ago in an era where events that happened just yesterday feel like outdated news?

The issue of the U.S. military comfort women is not a story of the past or something outdated. It is an ongoing issue. Despite continuous minimization, U.S. military bases still exist in South Korea, surrounded by base villages built for the convenience of U.S. soldiers. While most of these villages no longer house Korean women, foreign sex workers continue to work in them today. This makes it an issue that is still very much alive, and because it is politically sensitive, it is often not discussed. Within South Korea, it is an uncomfortable truth for everyone, regardless of political affiliation, and internationally, it is a difficult subject because it risks antagonizing the U.S. military, the dominant global power. However, how long can we continue to turn a blind eye to uncomfortable truths? Can we speak about South Korea’s present without addressing the U.S. military bases, which once occupied over 17% of its habitable land, or the stories of comfort women who, in the 1960s, generated 25% of the country’s foreign currency earnings? History that only represents the powerful, events not narrated from the victim’s perspective, and crimes that remain unresolved are not relics of the past but present-day issues.

Could you share any details about new media projects or upcoming works you are currently planning?

If it involves new media, my upcoming work will likely incorporate AI. The rise of anti-Asian hate crimes in the U.S. has been beyond imagination. This growing hostility in American society towards the "other" has prompted me to reflect deeply on two themes: discrimination and, conversely, tolerance toward those who are different. Although I cannot reveal specific details yet, I plan to integrate AI technology and mixed-reality (MR) techniques to create a psychological analysis of racial discrimination.

However, the next project to be completed will likely be the third and final installment of my U.S. military comfort women trilogy. While making Bloodless and Tearless, I felt a great deal of time pressure to capture the physical and geographical traces of the camp towns before they disappeared. As I prepare the third installment, that sense of urgency has only grown. Like the previous two works, space is a crucial element of this film, but the entire area is now on the verge of disappearing for various reasons. To visually restore parts of buildings and spaces that have been damaged and remain only partially intact, I am experimenting with digital restoration technologies and augmented reality (AR). Ironically, this might become the most visually striking of the three films.

Simultaneously, I am also developing a feature film on the topic of U.S. military comfort women. While working on the VR trilogy, I gained a tentative plan and the courage to explore this subject in a full-length feature. It has been exactly 30 years since the "Yun Geumi Incident" in 1992, and although it has taken a long time, this delay underscores the difficulty of dealing with the ethics of representation when working with a medium like film, which typically focuses on “showing” of things. The path that led me here was neither straight nor swift, yet it could not have been otherwise. As I have noted before, complex knots demand to be unraveled with equal complexity—with patience, persistence, and care.

This is an excerpt of Borderless Storyteller, originally published by the Jeonju International Film Festival. To learn more about, please click here!