Published December 5, 2023 - Full Article

December 2023 Issue, translated from Korean

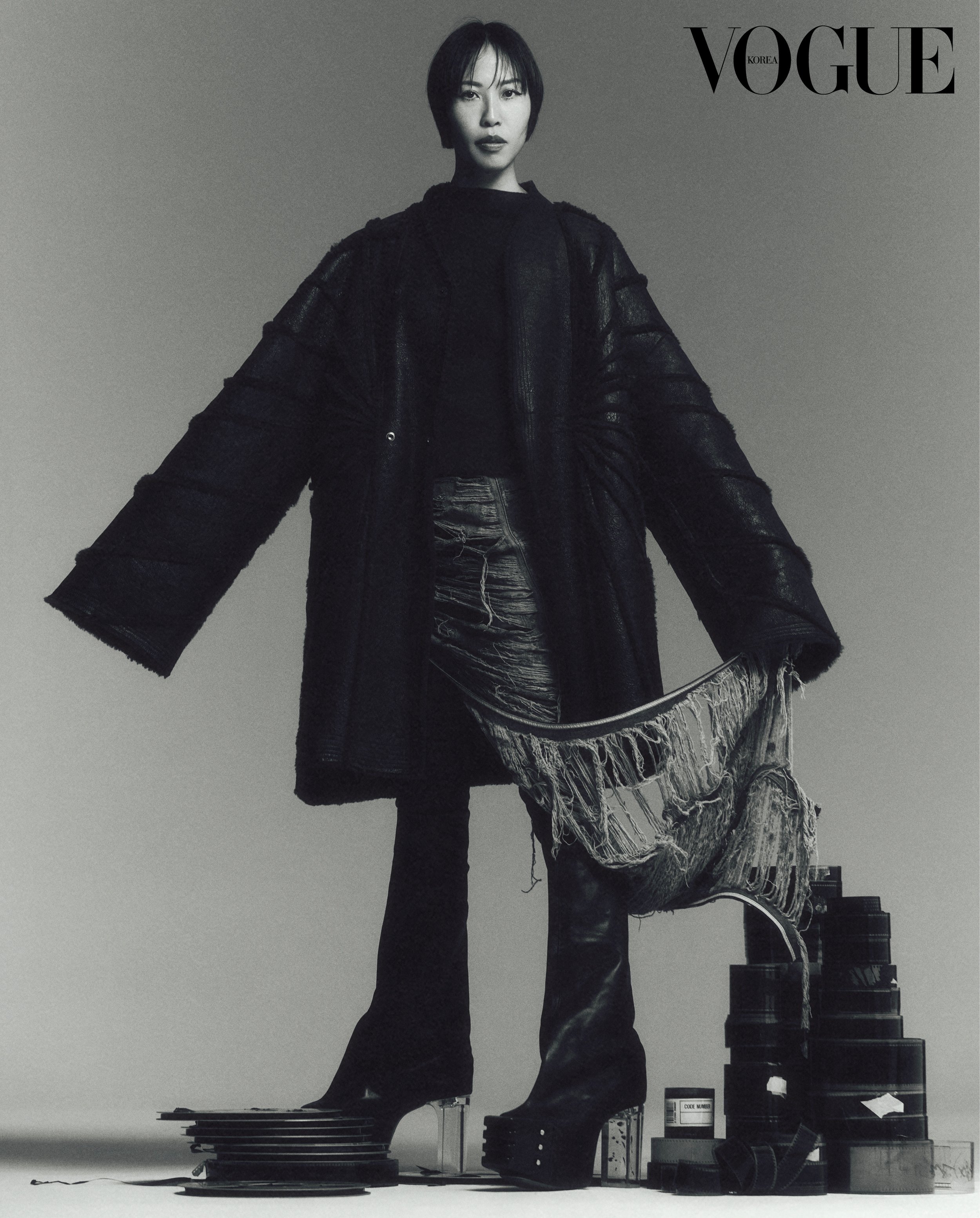

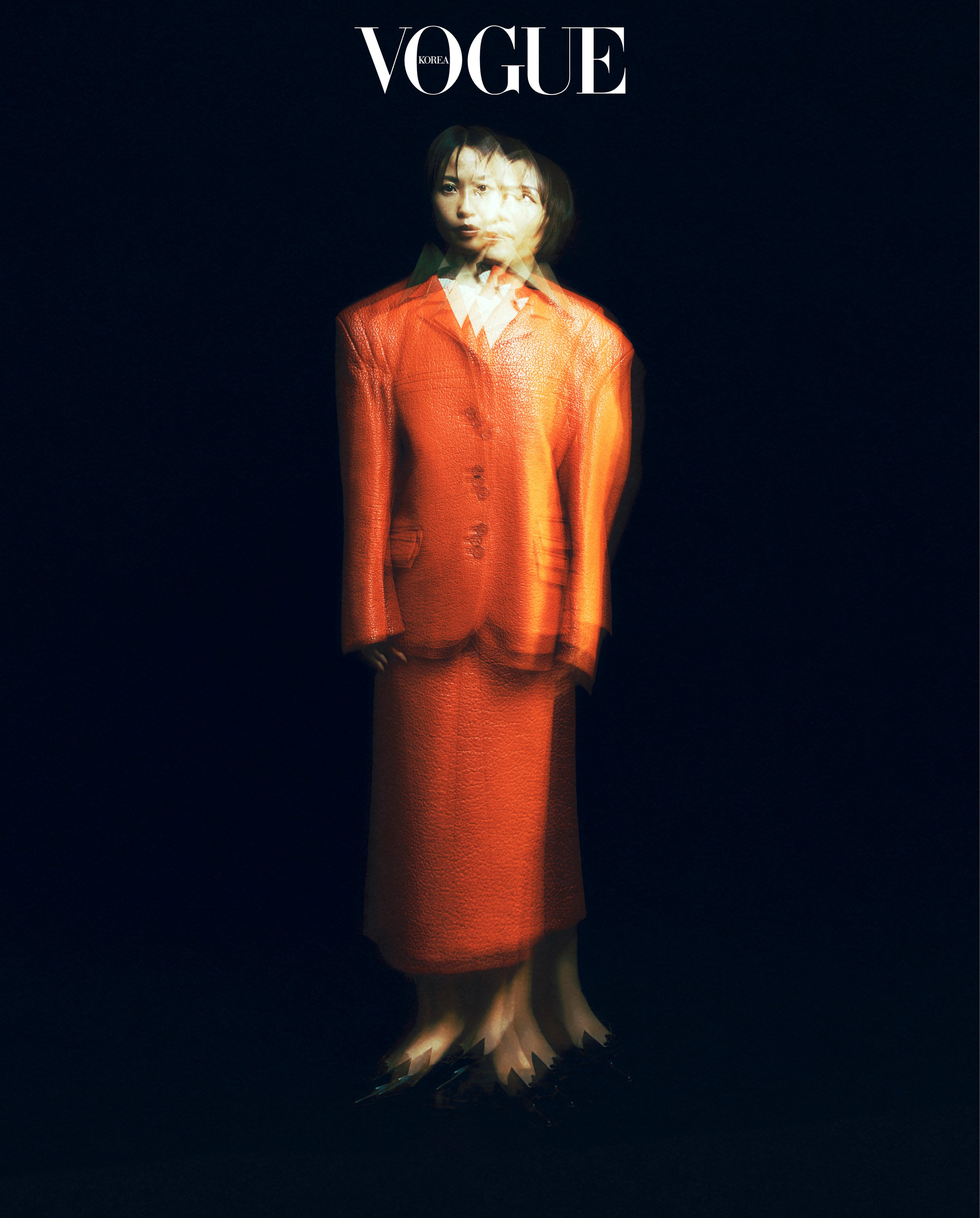

Comfortless Trilogy, an Expanded World Created by Director Gina Kim

No more silence. Breaking free from the rectangular frame, a 360-degree expanded world captures pain, sorrow, and fleeting happiness that had gone unseen. Gina Kim’s VR trilogy—Bloodless, Tearless, and finally Comfortless—relentlessly traces the haunting footsteps of U.S. military comfort women. Her meticulous storytelling becomes a quiet mirror, gently resonating with our own reflections.

Interviewer & Editor Ryu Gayoung

I experienced VR cinema for the first time through your work, at the special program Your Silence is a Mirror held at the Korean Film Archive. Audience members, equipped with VR headsets, were seated in swivel chairs and invited to rotate freely as they engaged with a series of immersive works, each approximately ten minutes in length.

Bloodless(2017), Tearless (2021), and Comfortless (2023) comprise a trilogy that marks the culmination of my eight-year inquiry into the lives of South Korean women subjected to military sexual exploitation near U.S. bases. As this chapter draws to a close, I was especially committed to presenting the works meaningfully in Korea. It was deeply rewarding to exhibit the full trilogy at the Korean Film Archive—a symbolic site that serves as both a guardian of national film heritage and a space for contemporary cinematic discourse. I am particularly grateful to Director Kim Hong-joon, who curated the exhibition and has long been a respected senior and unwavering supporter. He attended the Korean film retrospective I organized in 2005 during my tenure at Harvard, as well as last year’s special program at the Seoul International Women’s Film Festival. After viewing the trilogy, he became visibly emotional and said, “How do you create something that leaves one unable to breathe?” His words were profoundly encouraging.

You’re currently based in Los Angeles, but this exhibition allowed you to engage directly with Korean audiences over the course of three weeks. Were there any particularly memorable encounters?

I distinctly remember a woman in her early forties who wept throughout her viewing of Comfortless. She later told me her tears began to fall the moment she saw the peaceful rice fields in the opening scene. For her, the juxtaposition of pastoral tranquility with a site marked by exploitation was overwhelming. She described the silence of that landscape as lush—but unbearably heavy.

At its peak, 96 camptowns (gijichon)—zones servicing U.S. military personnel and deeply entangled with the comfort women system- were established in South Korea. Following your depictions of Dongducheon and the Soyosan medical prison (aka, Monkey House), your new work turns to the U.S. Air Force base in Gunsan.

Dongducheon camptown remains active to this day, while the Soyosan medical prison that locked up and treated US military comfort women stands in ruin, eerily reminiscent of a horror film setting. In contrast, American Town depicted in Comfortless presented a more ambiguous atmosphere. The area was largely deserted, though a few clubs still operated at night. The space didn’t initially lend itself to cinematic representation, and I struggled to determine how best to approach it. It felt suspended—neither entirely of the living nor the dead. There was a haunting liminality to it, as if one had entered a purgatorial zone of time and memory.

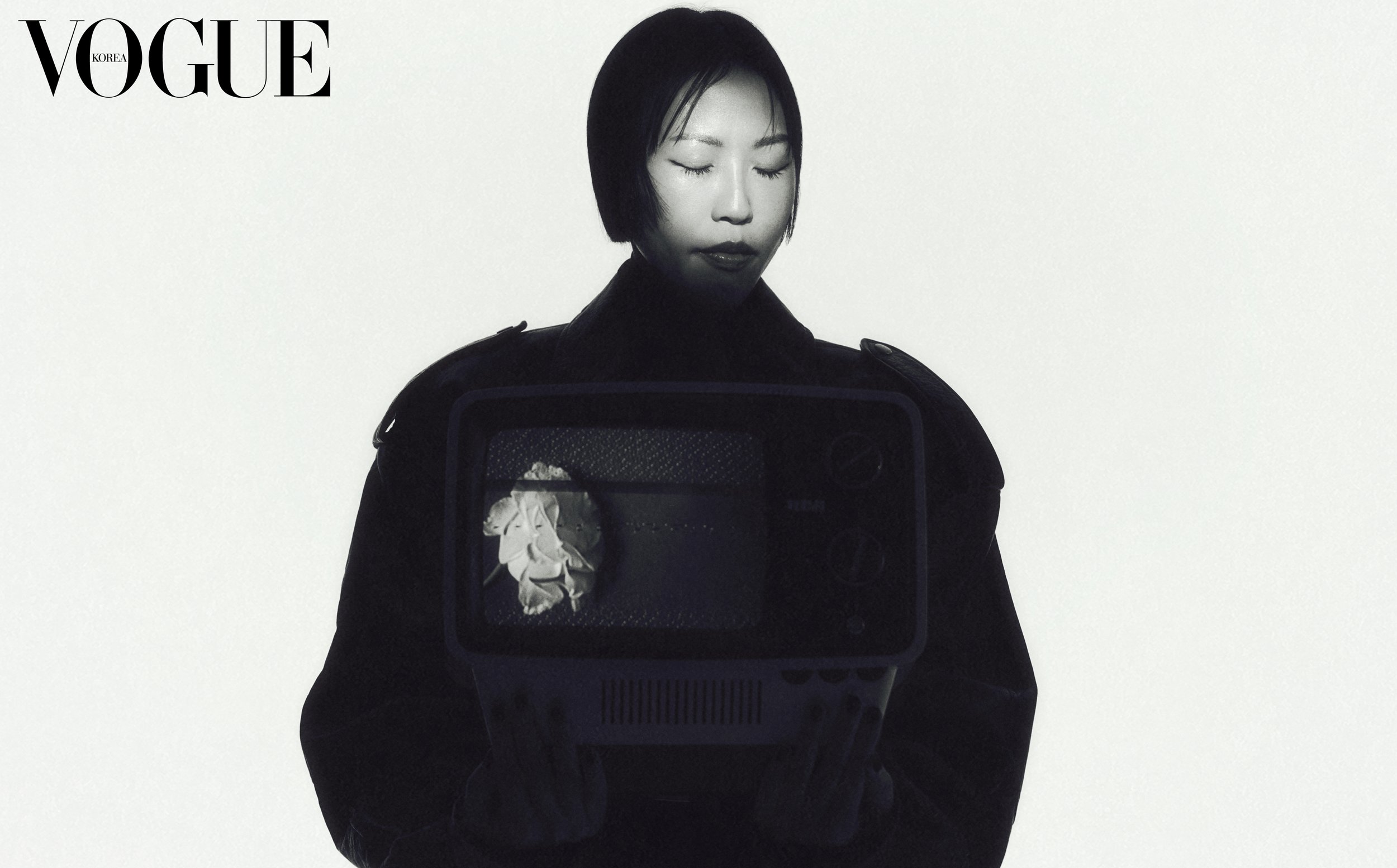

How did you arrive at a visual language for such an elusive space? In a 2023 interview with Vogue Korea, you hinted that Comfortless would be your most “visual” work to date. The use of mirrors, placed throughout the environment to project the protagonist’s past, stood out as a particularly compelling device.

I spent considerable time walking through the town, and what repeatedly caught my attention were the mirrors. In such an unpopulated area, I often startled myself upon unexpectedly catching my own reflection—an experience that felt curiously significant. Mirrors, of course, are potent symbolic instruments: they reflect not only what is in front of them, but also what lies behind. Eventually, a clear conceptual thread emerged—the past is the mirror of the future.

Over the years, I have experimented with a range of technologies and media to render unresolved social histories present without replicating the gaze of exploitation. Yet I have continually encountered limits in translating that memory into transformative engagement. Paradoxically, it was the primitive optical tool of the mirror that began to suggest a way forward. In Comfortless, the mirror that might typically reflect the viewer instead reveals a past image of the female protagonist. The moment a viewer gazes into a mirror and does not see themselves, but another—someone from the past—triggers a visual and semiotic dissonance. I found that shift in perception to be a profoundly generative space for participation and reflection.

Unlike the previous two works, Comfortless features a striking departure: for the first time, the protagonist addresses the viewer directly, asking, “Who are you?”

Many camptowns still remain, and countless untold stories persist. As the final work in the trilogy, I felt a need for a mechanism that could reframe the issue of U.S. military comfort women as a problem of the here and now—as something personal. The world seen through a mirror in Comfortless is, in many ways, jarring. But because it is perceived as a world within the mirror, Comfortless allows viewers to maintain a certain psychological distance from the tragedy, much like watching a film or drama. However, in the moment when the woman steps out from behind the mirror, becoming a tangible presence who poses a direct question to the viewer, her dilemmas become our own.

Who are you—the one who follows her, silently witnessing her most intimate and vulnerable moments? Who are you—the viewer from the 21st century, donning a VR headset to sensorially experience and observe the camptowns of the 1980s? These are the questions I wanted to provoke.

You seem to hold a strong sense of responsibility toward documentation and archiving, often emphasizing the power of documentary as a mode.

Everything is disappearing too quickly. One of the most challenging aspects of the lawsuit against the state filed by US military comfort women has been the passing of key witnesses. If all evidence vanishes, what will remain for us to fight with? The entirety of American Town is undergoing rapid demolition as part of redevelopment efforts, and so is Monkey House. Soon, everything will be gone.

This urgency led me to create not only three VR films but also an AR (Augmented Reality) work. With AR technology, it’s possible to archive spaces—and once a site is digitally scanned, future viewers can virtually wander through the vanished camptowns anytime, anywhere. That kind of immersive archival becomes a way to resist erasure.

When I first put on the VR headset, I was anxious about missing meaningful moments. After eight years working with emerging technologies, do you feel the journey has been rewarding? Or were there technical limitations that left you unsatisfied?

The low resolution of the image remains a significant issue. There’s also the problem that without the device, the work is simply inaccessible. The physical discomfort of wearing the headset also limits broader participation. These factors have certainly curtailed the reach of the experience. The COVID-19 pandemic brought another blow. When all the theaters and museums capable of hosting VR content shut down, only niche communities like gamers and K-pop fans watching ultra-HD concert footage maintained access to the technology.

The initial excitement surrounding new media faded after the pandemic. Around 2016, there was a global VR boom—VR journalism seemed to offer a new frontier for documentary storytelling. But that field has largely vanished now, which is deeply disappointing.

You’re currently immersed in adapting Princess Bari, a novel by author Hwang Sok-yong, into a feature film. After Never Forever (2007) starring Vera Farmiga and Ha Jung-woo, and Final Recipe (2014) with Michelle Yeoh and Henry Lau, this marks your return to commercial cinema.

I was in the throes of preparing Comfortless for its Venice Film Festival premiere when I was contacted by a British producer. I hesitated, uncertain I could do justice to such an expansive narrative of Princess Bari. But the producer insisted, even traveling to Venice to meet me (laughs)!

Later, I had the opportunity to meet Hwang Sok-yong in Korea. To my surprise, he had read every one of my interviews—even those conducted in English. He said my thinking, especially around transnational consciousness, resonated strongly with the themes he had grappled with while writing the novel. He was particularly moved by my critique of how women’s bodies are subjected to violence when imperialism and capitalism intersect. Princess Bari, which centers on a North Korean defector, explores exactly that dynamic.

After studying fine art in Korea and film in the United States, you’ve explored a range of modes—from visual art, experimental cinema, and documentary to narrative film and VR. What kind of longing or tension drives this eclectic trajectory?

The medium has always followed the message. Once I become fixated on a story I want to tell, I choose the medium that best suits it—this is how my creative spectrum has naturally expanded. Certain themes have persistently preoccupied me at different stages of life: the female body, diaspora, the imperialism of language. Immersing myself in these, I’m sometimes led to a performance piece, at other times to a cinematic sequence. I’ve also always been driven by a deep curiosity about new technologies and modes of expression.

Gina Kim’s Video Diary (2001) is a 157-minute video essay composed of six years of intimate footage. It delves into deeply personal themes such as diaspora, anorexia, femininity, and familial history. The narrative begins at age twenty-two, the moment you decided to leave Korea.

Despite opposition from my intellectual parents, I entered art school — but I couldn’t envision a viable future as a female artist in Korea. It felt impossible. Beyond the widely publicized Yoon Geum-i case, there were other horrific incidents: a young woman repeatedly raped by her stepfather (whose murder by her boyfriend was an act of defense), and repeated systemic failures to protect women. There was also the sexual harassment case at Seoul National University. The violation of women’s bodies seemed relentless.

I felt there was no place for someone like me in this society. Issues of labor and class are framed as battles to be fought, but an anorexic woman starving herself to death is dismissed as vanity. The public discourse on human rights felt narrow and suffocating. At twenty-two, standing before a wall that seemed insurmountable, I decided to leave. I didn’t know how else to resist.

How do you respond to the pain of others? In Regarding the Pain of Others, Susan Sontag called for a kind of compassionate witnessing—a refusal to be indifferent to suffering.

The first reaction to witnessing someone else's pain is emotional—grief, anger. But these feelings can easily devolve into complacent gratitude: “At least that’s not me.” Worse still, they can lead to the exclusion of the person who suffers—a second, subtler violence.

To avoid this, I try not to be swayed by emotion alone. I ask myself, with clarity and calm: What can I do, here and now, for the person in front of me? I don’t want to be a warm person. I want to be a cool-headed one. Empathy requires more than just feeling—it requires thought, commitment, and action.

What does ‘justice’ mean to you? Do you believe cinema can achieve it?

The word justice often carries a whiff of sanctimony. At times, horrific acts are committed in its name. So rather than defining justice (in the sense of “to define”), I believe in fostering a culture where justice (as in “to pursue”) can be widely discussed and contested. (*The Korean word jeong-ui (정의) is a homonym that carries two meanings: "definition" and "justice.")

A good film doesn't pretend to deliver answers. It asks essential questions. Even if viewers leave feeling unsettled or confused, such a film holds value—because it pushes us to revisit something we may have forgotten.

You have a longstanding relationship with the Venice International Film Festival—Bloodless won the Best VR Story Award, and you were the first Korean woman filmmaker to serve on the jury for the feature film competition in 2009. You recently returned to Venice wearing a bold yellow Loewe dress to present Comfortless. What kind of cinema do you hope the world will see more of?

The tradition of the nude in art emerged as a form of male painters objectifying women. Similarly, colonial authorities photographed Indigenous subjects to assert control. Today, tourists from the first world photograph children in the third world with casual entitlement. Cinema, too, is entangled in the history of power. The films I want to see are those in which the formerly objectified step behind the camera and claim authorship. Such films make us uncomfortable, but we need more of them. We need cinema that reveals inconvenient and uncomfortable truths.

You currently teach film at UCLA. You were also the first Asian woman to teach in Harvard’s Department of Visual and Environmental Studies, and Variety named you one of the top film educators in the U.S. What thoughts come to mind as you watch your students grow?

It’s terrifying (laughs). The students I taught twenty years ago are now senior executives at global tech and media companies, making decisions that shape our culture, our platforms, and our policies. Some even cite ideas we explored in class when advocating for policy change in government or cultural institutions.

It’s a sharp reminder of the weight of what we do as educators. We plant seeds—but we must also know what we are planting. I never step into a classroom without a clearly defined intention. That said, I’ve also gained a great deal from this demanding environment—endless learning, inspiration, and creative energy. My students keep me aligned with the present moment. I’m grateful that they help me remain an artist of this time.

Your social media occasionally offers glimpses into your life in the U.S.—especially the lush farm you’ve cultivated. It seems to bring you a lot of joy.

It might be the thing I’m most proud of (laughs). During the pandemic, out of laziness, I buried some food waste — like fruit peels and unwanted vegetable parts that usually go into the green recycling bin — in the backyard. When they started to sprout, I was so moved by their vitality that I began gardening in earnest. Now it’s become a forest.

There are at least fifty kinds of crops growing, and when the flowers bloom, petals fall like rain—I have to shovel them off the ground. It’s a tremendous amount of daily work, but when I sit in the study and watch the leaves and blossoms flutter, I feel completely cleansed. It’s a happiness I can’t find anywhere else.

And now the garden welcomes visitors, too: bees, butterflies, doves, hawks, squirrels, raccoons, and even opossums. I didn’t use any pesticides or special tricks—just created a good environment, and everything else took care of itself. Isn’t that amazing?

Could your next project be a gardening book instead of a film?

That would be fun. There’s always something happening out there. Watching the garden transform into its own ecosystem gives me a deep reverence for life. To witness how something draws nourishment and persists in living—that’s always extraordinary, always tender.