[Marie Claire Korea] - Resistance and Subversion

Published 2022 - Source

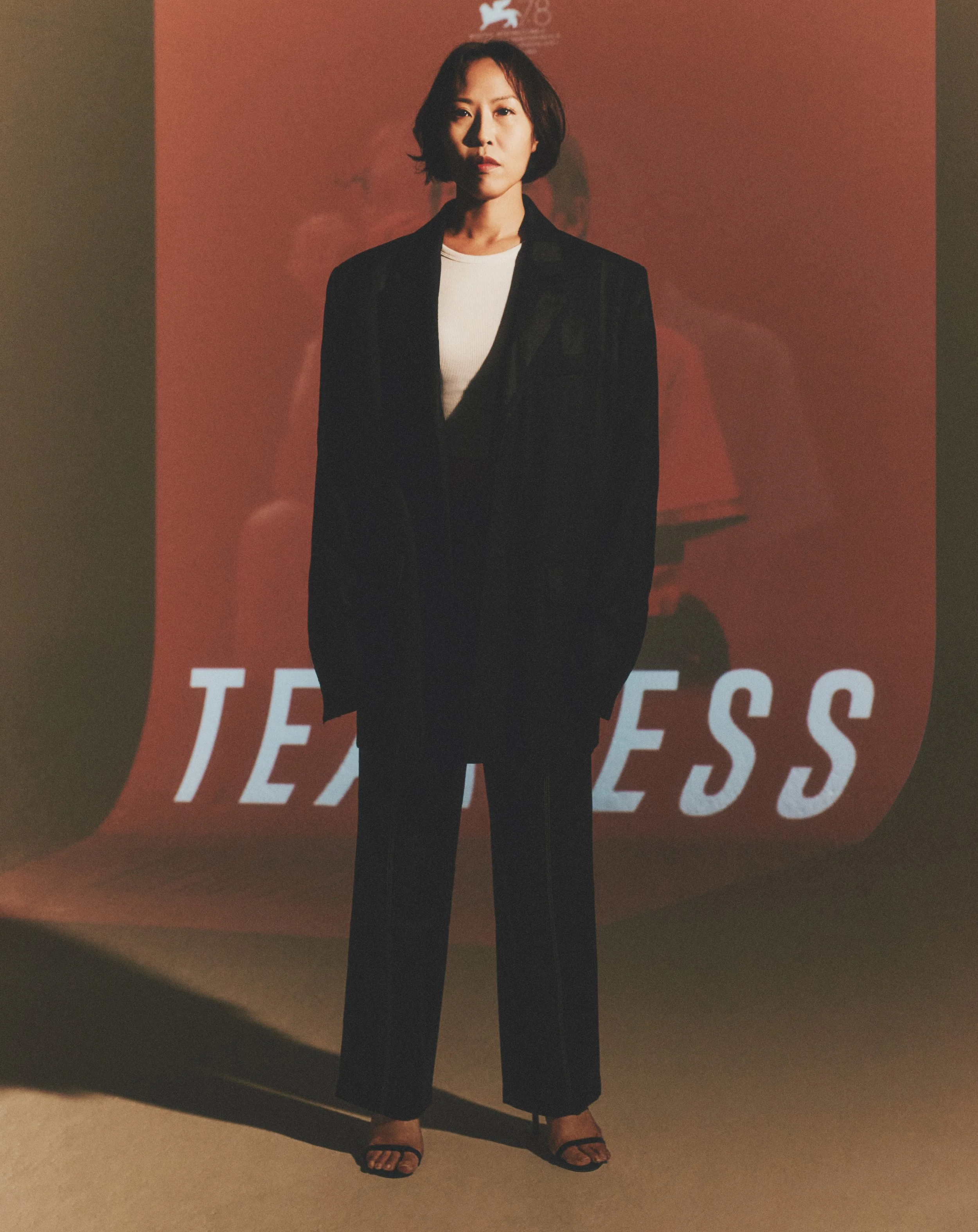

Editor Kang Ye Sol, photographer Chae Dae Han

Translated from Korean

“Making films, for me, was a response—a resistance—to the way images are shaped.”

— Director Gina Kim, on the ethics of representation

The horror and pain of encountering a photograph of a brutally murdered woman—killed by a U.S. soldier stationed in Korea in 1992—never left Gina Kim. That moment, and the sense of moral debt it triggered, have remained with her throughout her 20-plus-year filmmaking career. She had always wanted to tell this story—without exploiting the image of the victim, without presenting it through a sensational lens. Her search for an ethical medium finally led her to virtual reality (VR). Seeking a form that would move beyond the stereotypical image of a victim, she found a way to approach the profound loneliness and pain endured by a real human being. Thus began her journey toward the Comfort Woman Trilogy.

Two of the three VR works in this trilogy, BLOODLESS and TEARLESS, have now been released. While both have already screened at some of the world’s leading film festivals and won awards, this special showcase at the Seoul International Women’s Film Festival (SIWFF) holds a distinctly different meaning.

Absolutely—it feels very personal. I first screened my graduate thesis short film Empty House at this very festival in 1999. Later, my first feature Invisible Light received an award here, and Bloodless also had its premiere through SIWFF. Beyond these personal milestones, this special program holds profound significance for me. It tells a story about Korean women—one that remains urgent. Sex work catering to U.S. military personnel continues to exist, and as recently as two decades ago, Korean women were still engaged in that labor under state complicity and silence. To be able to share this history with young Korean women today—to make space for remembrance, reflection, and dialogue—is deeply meaningful. I am sincerely grateful.

There are also several programs planned outside the film screenings themselves—ways for audiences to experience the story with their whole bodies.

We will begin with Bloodless and Tearless. As VR works, these films are not presented in conventional cinemas but in specially designed immersive spaces that allow for embodied, spatial engagement. For those unable to attend the festival in person, we have developed a companion app that offers AR and XR versions of the environments depicted in the films—providing an alternative way to enter and explore these charged spaces. In conjunction with the screenings, a special talk event is planned, offering an opportunity to reflect on the motivations behind these works and to engage in a broader conversation about how gender-based violence can be ethically represented through immersive media.

The trilogy is thematically connected through one subject: “U.S. military comfort women.” The series begins with the story behind BLOODLESS—the 1992 murder of Yoon Geum-yi (a bar worker in the U.S. military camptown of Dongducheon who was killed by a U.S. Army private), right?

That’s right. The incident took place in 1992, during my first year of college. I participated in the wave of protests that spread across the country, and for a moment, it felt as though something had shifted: for the first time, the perpetrator of a crime committed in a camptown was tried in a Korean court. And yet, what remained deeply unsettling for me—and for many women of my generation—was the widespread circulation of a photograph of the victim’s body. Even in the name of justice, the image felt like another violation. I carried a heavy sense of guilt, a quiet horror at the fact that her body had to be sacrificed yet again—visually, publicly—in order to be seen, to be acknowledged. In that moment, I made a promise to myself: that one day I would tell this story, but in a way that would not reproduce harm. That I would find a form that honored her life without exploiting her death.

So were you waiting for the right moment? Why tell this story now?

It wasn’t that I was waiting for the right moment—I was searching for the right form. Because to speak of violence is, at times, to risk enacting it again. I made several attempts over the years. As I moved into narrative filmmaking, it felt natural to try to tell this story through fiction. I even pitched versions of the script to production companies. But within the framework of commercial cinema, I kept encountering the same limitation: the narrative would inevitably center on a male detective, or the male perpetrator, while the woman would be relegated to a passive symbol of victimhood. That structure, that gaze—I couldn’t accept it. So I kept trying, and then letting go.

In 2016, I encountered VR for the first time, and something shifted. I realized this might be a medium where I could finally tell the story—without showing the incident itself. That may sound contradictory, but it was precisely that paradox that opened up a new space of possibility. A way to approach trauma without reproducing it.

Is that why you chose “the absence of the body” as a central motif for the U.S. military comfort women trilogy? Because these are works that address gender-based violence without showing the body.

Yes, this project began from a deep sense of injustice—specifically, the widespread circulation of photos of the victim’s body, and the guilt I felt in having seen them. From the outset, it was clear to me that this story could not be told through images that re-enact or sensationalize the violence. It was essential not to exploit the victim’s image, but to bring the issue into public consciousness through a form that respects her dignity. The challenge was to create a space for ethical remembrance—one that would confront the violence without reproducing its logic.

Were there any specific principles or guidelines you followed during the production process?

While working on Bloodless, I had hoped to recreate the room where Yoon Geum-i had lived. To my surprise, the building was still standing. There were, of course, no visible traces of the incident, but I felt a strong desire to film at the actual site. At the same time, it was essential to respect the people currently living there. In the end, I let go of that plan. Every stage of the process involved careful deliberation with the team: what was the most ethical choice? That question guided every decision.

The same care shaped the making of Tearless. Unlike Bloodless, this piece doesn’t center on a single individual, but on the “quarantine camps” built by the South Korean government to isolate and treat comfort women suspected of having venereal diseases. The most difficult question during production was whether to reconstruct the facility. The building still stands, but in a state of extreme neglect—strewn with remnants of homelessness, debris left behind by YouTubers, and other unspeakable traces. I asked myself: is it right to intervene? Is it ethical to restore or even clean such a place?

In the end, we established a guiding principle: we would not disturb anything that was originally part of the site—not even a shard of glass. We would only remove objects brought in by those with no connection to its history. What sounds simple was, in practice, incredibly difficult. We didn’t shift a single broken tile. And yet, the team embraced this decision with full understanding. That shared commitment made the work possible.

It seems like maintaining ethical standards during the filmmaking process was just as important as the final result.

We truly poured everything we had into this work. (laughs) And if we’re being honest, there’s no end to the ethical dilemmas. One could argue, quite reasonably, whether making a film like this is justifiable at all. These are difficult questions with no easy answers. But what I can say, with clarity and conviction, is that we did everything in our power to approach the work with care, integrity, and responsibility. We did our best.

What did you most want to express in the structure of the narrative itself?

With Bloodless, I focused on poetically evoking the final moments of Yoon Geum-i’s life—just those last few minutes. I wanted to follow the emotional path she might have taken, above all the profound loneliness of dying alone. Time and space were structured to reflect that sense of isolation, creating an atmosphere that allows the viewer to feel, rather than merely observe, the weight of that solitude.

In contrast, Tearless is not centered on a single individual, but on the collective emotional experience of the women confined within the quarantine facility. What struck me most on my first visit was the institutional timetable still posted on the wall: 7 a.m. wake-up, 8 a.m. breakfast, 10 a.m. treatment. That schedule—so mundane, so mechanical—became a key through which I approached the film. It offered a framework to imagine and reflect on the daily suffering endured by these women, whose lives were reduced to a regimen of control and silence.

Working in VR must have been completely different from narrative filmmaking. Were there things you learned through the process?

Absolutely. I didn’t come to VR with a background in immersive technology or a long history of experimentation—I learned everything from scratch, simply because I needed this medium to tell the story I had carried for so long. I truly started from zero, and naturally, there were many humorous moments along the way due to my lack of technical knowledge. I still remember one early location scout: after filming a segment, I confidently said, “Okay, now let’s shoot the back,” and someone gently reminded me, “Director—it’s a 360-degree camera. We already did.” (laughs) That concept took a while to fully register, and I made that same mistake more than once.

Even my approach to composition had to shift completely. In traditional filmmaking, you rely on coverage—wide shots, close-ups, and editing to direct attention and emotion. But in VR, those tools don’t function in the same way. You have to think differently: how will the viewer move through the space? What will they see—or miss? Where will their attention naturally be drawn? You’re not just constructing a scene; you’re designing an environment for experience. That shift was both humbling and exhilarating.

It sounds like you had to rewire your instincts.

Exactly. I think that’s why many filmmakers try VR and then step away from it—it can be disorienting at first. For me, the transition was confusing at the beginning, but I adjusted quickly. I realized I had already encountered something similar years ago, during my time in college, when I directed experimental theater. There’s a particular format in that tradition where the audience sits at the center of an empty space, and actors enter from the periphery, deliver their lines, and then disappear again. Once I began to think of VR in those terms—as a kind of immersive, spatial theater—the logic of it became much clearer to me. It stopped being foreign, and started to feel intuitive.

In another interview, you said the aesthetic basis of VR isn’t voyeurism, but experience. But that seems like a privileged, ethical directorial stance—not everyone approaches VR that way.

That’s true. Media, in itself, is neutral—there’s no inherently right or wrong media. When VR first emerged, there was a wave of concern. Like many new technologies, it was quickly pulled toward pornography and violence, and early VR was no exception. But from my experience working with the medium, I’ve come to believe that voyeurism is actually quite difficult in VR. The moment you put on the headset, you lose your body. You can’t act, only observe. In that immersive space, you are profoundly vulnerable—disembodied, disoriented, and exposed. From that position, the act of enacting violence, or even assuming a voyeuristic gaze, becomes strangely inaccessible.

In VR, the usual hierarchies of power—the ones reinforced by traditional cinematic grammar—begin to dissolve. You are no longer a distant spectator controlling the frame; you are inside a world you cannot manipulate. That’s when I began to see VR as a medium uniquely capable of representing the marginalized—those who have historically been denied agency and voice in audiovisual media. Not because it erases violence, but because it restructures the conditions of seeing and being seen.

And you’ve already seen a range of reactions from international film festivals. I heard that responses differ by race and gender.

They do—almost to the point where you could map the responses on a chart. The divide wasn’t primarily about class, but about race and gender. Korean women, in particular, reacted with visible fear and unease. White men, by contrast, showed little to no fear at all. The disparity was so striking that it stayed with me. It became clear that the work wasn’t just speaking to gender-based violence—it was also revealing the deeper structures of violence produced by the contradictions of late capitalism and postcolonial power. And the way different bodies respond to that violence—whether with fear, detachment, or denial—is not merely social or rational. It’s something inscribed in the subconscious. A long inheritance of who feels safe, and who doesn’t.

This work, which began from a sense of moral debt, is now approaching its final story. Has that weight you've carried for so long lightened at all?

I don’t believe it has. The deeper I delve into this history, the more overwhelmed I am by how thoroughly it has been buried—sealed away from public discourse. If this were a case that could be easily framed as the fault of a single perpetrator or placed solely on the shoulders of the U.S. military, perhaps it would have been easier to confront. But the reality is far more complicated. Korean society, too, bears responsibility. Under the military dictatorship of the time, there were even state policies that actively encouraged prostitution in camptowns.

The lives of women in these spaces destabilize many of the moral and ideological frameworks we rely on to make sense of the world. To speak about their experiences is to ask uncomfortable questions: What constitutes sexual service? Is it prostitution, sex work, or sexual slavery? These are not just terminological debates—they reveal the limits of our language and the discomfort we feel when that language fails. And because camptowns still exist today, the subject remains politically and socially fraught.

Still, I believe that our silence has become part of the violence. Avoiding the conversation does not make it go away. On the contrary, it deepens the erasure. To speak, however imperfectly, is at least to begin the work of acknowledgment.

Looking back at your body of work since the 1990s—narrative films, documentaries, VR—you’ve moved between media, but one thing remains constant: a resistance to injustice.

Yes. In retrospect, I realize that I’ve been preoccupied with the ethics of representation from the very beginning of my practice. Early on, I was deeply unsettled by the ways in which women’s bodies were depicted in film—how they were framed, consumed, and often stripped of agency. In response, I turned the camera on myself and began experimenting with performance-based video art, which eventually became Gina Kim’s Video Diaries.

Invisible Light emerged as a direct reaction to patriarchal stereotypes—I wanted to portray female desire not as an object of voyeurism, but as an autonomous, inner force. Never Forever was shaped by a different impulse: to challenge the Western media’s narrow, often emasculating portrayals of Asian men.

What underlies all of these works is a critical awareness of power. Traditional filmmaking—like much of visual culture—invests control in the person behind the camera. The subject, often a woman, often someone without wealth or voice, is granted little to none. This hierarchy is not new; it stretches across art history and remains embedded in the visual codes we inherit. I think my entire body of work has been, in one way or another, an effort to resist and subvert that structure—to find ways of working within, and against, the systems I inhabit.

Do you think this resistance comes from something innate? Or was it shaped by your experiences?

Perhaps a bit of both. I came of age during a time when student activism was still a powerful force, so from an early age, I was acutely aware that injustice wasn’t something to be observed passively—it had to be challenged. As a child, I often found myself asking why the world was so full of suffering, why things felt so profoundly unfair. Meanwhile, I was attending school, eating well, living comfortably. And I felt guilty.

My father once told me that guilt is a sign of conscience—that it means you have a sense of justice. He also said that privilege is only justified when it’s used to help others gain access to the same. I heard similar things from mentors I met in college. Over time, that sense of responsibility became deeply internalized. For me, this resistance—this work—is not just creative expression. It feels like a kind of moral tax I owe the world. A way of honoring the fact that I’ve had choices, and using those choices to speak where silence has prevailed.

And now, like your father and those mentors, you’re passing on those values to a younger generation. You're not only a filmmaker but a professor, too.

That’s right. I try to pass on what I’ve learned in ways that resonate with the present. Many of my courses center on media for social change. Last semester, for instance, I taught a class that used augmented reality to visualize anti-Asian hate crimes—an attempt to engage students with both history and technology in a way that feels immediate and embodied.

I often find myself repeating something my father once told me: that privilege must be used to expand access for others. And I add one of my own: don’t act with arrogant self-importance. It’s easy to fall into the illusion that you’re doing something exceptional or singular. But I remind myself—and my students—that I’m not the only one doing meaningful work, and that my way isn’t the only path forward. Above all, I hope they remain grounded, stay humble, and keep questioning. I try to do the same.

If all the injustices and violence in the world disappeared, would you stop making films?

If a utopia like that ever came true? It’s a question about my desires too—and honestly, yes, I think I’d still make films. Just… happier ones. The things that bring me the most joy are gardening and observing nature. I imagine making films about rainbows, or documentaries following baby birds as they grow and learn to fly. Maybe even VR pieces about soil and earthworms—quiet, patient studies of life below the surface. Even just imagining it brings me peace.

You really lit up talking about gardening.

(Laugh) Did it show?