[Vogue Korea] - Women Who Must Be Remembered: The Reckoning of VR

Published January 3rd, 2022 - Source

Editor and interview by Narang Kim

With Tearless, the second chapter in her VR trilogy following Bloodless, director Gina Kim continues her searing exploration of the painful histories of marginalized women. These works are not only recognized by major international film festivals but also open up an urgent, alternate path for the future of virtual reality—one rooted in testimony, empathy, and the ethics of presence.

In November of last year, director Gina Kim’s VR work Tearless won the top prize in the Virtual Reality Competition at the 27th Geneva International Film Festival. It is the second installment in her VR trilogy about U.S. military “comfort women,” following Bloodless, which revisited the 1992 murder of a camp town sex worker by a U.S. soldier—a case that shocked South Korean society. Bloodless received the Best VR Story Award at the 74th Venice International Film Festival in 2017. Notably, in 2009, Gina Kim became the first Korean female filmmaker to serve as a juror in the feature film competition at Venice.

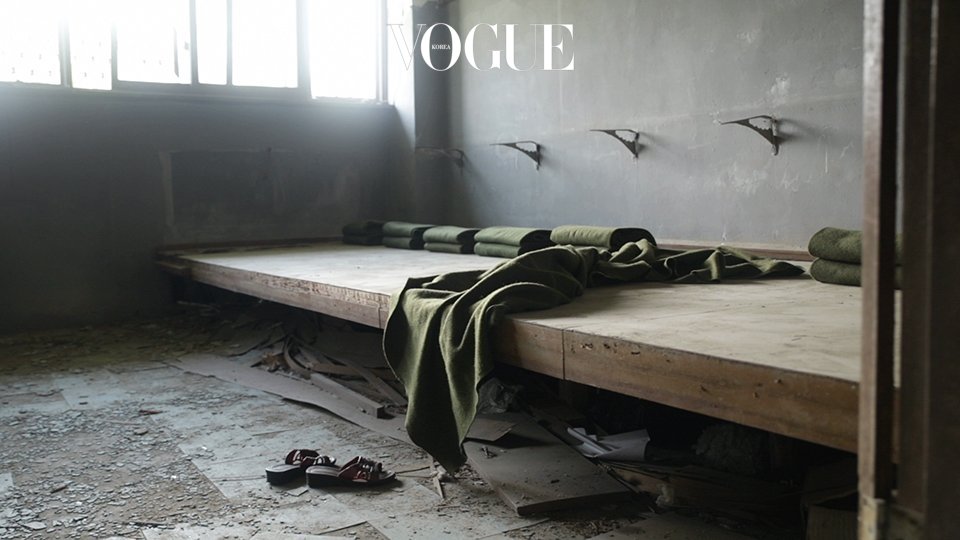

Tearless is set inside the infamous “Monkey House,” a detention and treatment facility established in the early 1970s by the South Korean government and operated by the U.S. military to isolate and treat camp town women suspected of carrying STDs. Viewing Tearless through a VR headset is an intense experience. From the moment one enters the fully reconstructed 360-degree space of the Monkey House, a cold sweat breaks out. When met with the hollow gaze of a woman (portrayed by actress Kim Bo-ryeong), it becomes difficult to move. This visceral experience can be encountered at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA) in Seoul in 2022.

The phrase “the first Asian woman to…” often precedes Kim’s name. After receiving her BFA in Fine Art from Seoul National University in 1996, she earned an MFA in Film from CalArts in 1999. She became the first Asian woman to teach in the Department of Visual and Environmental Studies at Harvard University, and she is currently the first Asian woman to hold a tenured professorship in the Department of Film at UCLA. As a filmmaker, Kim has worked across genres with a diverse body of work. She made her debut with the short Empty House (1999), followed by the experimental documentary Gina Kim’s Video Diary (2002), a diary-based chronicle of her life abroad from 1995 to 2000. Her first narrative feature, Invisible Light (2003), centers on two women—one struggling with an eating disorder and the other with an unwanted pregnancy.

Her 2007 feature Never Forever, starring Vera Farmiga and Ha Jung-woo, is a melodrama exploring love across boundaries of race, nationality, and class. As the first U.S.–Korea co-production, it garnered attention for being produced by Lee Chang-dong and featuring a score by Michael Nyman. In 2009, Kim directed Faces of Seoul, a video essay documenting the rapid transformation of the city from the 1995 Sampoong Department Store collapse through 2009. Its narration was later published as a trilingual photobook in Korea, France, and the U.S. In 2014, she directed the Korea–China co-production Final Recipe, starring Michelle Yeoh and Henry Lau, which premiered as the opening film of the Culinary Cinema section at the Berlin International Film Festival and screened in over 3,000 theaters across China.

VR became Kim’s next frontier. Haunted by the burden of history—the ways in which women have been consigned to pain by systems of violence—she had long wished to make a film about these themes. For 25 years, she attempted to do so through narrative cinema, but always encountered ethical challenges around representation. VR offered a different path. Rather than staging other people’s suffering as spectacle, VR allowed her to craft spaces of experience. Through Bloodless and Tearless, Gina Kim is not only pioneering new cinematic forms, but also telling stories that must not be forgotten—stories of women who endured, resisted, and still remain largely invisible.

Bloodless and Tearless are the first two works in your VR trilogy on U.S. military camp town women. You were a college freshman in 1992 when you first encountered the murder of a camp town woman by a U.S. soldier. The photograph of her mutilated body was made public to galvanize awareness. You’ve spoken of the guilt you felt witnessing how her body was instrumentalized. Was this 25-year sense of indebtedness the starting point for your trilogy?

Yes, I would say that this deep sense of debt was the origin. At the time, the university campus was plastered with protest posters, and the incident was also being leveraged for political purposes. My female peers and I found ourselves stunned, standing silently in front of the placards. The brutality of the murder enraged us, of course—but what overwhelmed us more was the fact that the victim’s image had been endlessly reproduced and exploited in the name of causes that had little to do with her as a person. At the time, I lacked the language and theoretical tools to explain my outrage. That unspoken, unprocessed anger gradually turned inward, becoming a gnawing sense of guilt—toward my own helplessness, and ultimately, toward the victim herself.

Your filmography spans a wide range—from the commercial Korea-China co-production Final Recipe, to personal essay films like Faces of Seoul, and now VR works. You once said, “Because I come from a fine arts background, my attitude differs from most directors. Rather than aspiring to make commercial feature films, I choose the medium that best fits what I want to express—whether that’s a crayon drawing, an oil painting, or an installation.” Why VR for Bloodless and Tearless?

When I first encountered VR in the fall of 2016, what struck me immediately was its aesthetic premise: unlike 2D film, which is based on voyeurism, VR is rooted in experience. The psychological mechanism that allows us to enjoy a feature film, no matter how violent or devastating, is rooted in voyeuristic distance. We can munch on popcorn while bombs explode or zombies devour bodies—because the screen acts as a psychological barrier. In VR, that barrier collapses. Though the world may be virtual, audiences feel physically present inside the narrative space. The moment I understood that essential difference, I realized that I could finally tell a story I had been trying—and failing—to make for over two decades. With VR, I could re-create the space of the incident in a poetic, sensory manner and offer it not as spectacle, but as experience.

Tearless is set in the so-called “Monkey House,” a detention center established in the early 1970s by the Korean government and operated by the U.S. military to isolate and treat women suspected of having STDs. Viewers enter the 360-degree space via VR headset, encountering its dormitories, toilets, dining areas, and treatment rooms. I understand you discovered this building during your research for Bloodless. What was your reaction when you first encountered it?

The Monkey House—officially known as the Soyo Mountain detention center—was a critical site, one that surfaces anytime the issue of U.S. military comfort women is addressed. It was the first place I visited during my research. My initial reaction standing in front of the building was disbelief: “How is this still here?” It wasn’t simply the decay—it was the palpable sense that something unspeakable had occurred there. The atmosphere was so oppressive that some crew members refused to go inside. The interior was strewn with filth: torn bedding, old car parts, and every imaginable kind of trash. When I first visited in 2016, the wooden doors were still intact, but by my next visits, they had been ripped out one by one. The graffiti grew more invasive. After the torrential rains of 2020, I began to fear the structure might not survive much longer. Producer Zoe Sua Cho remarked the same: while it would be horrifying if this place had disappeared without a trace, the fact that it still stood in such a state of erasure was equally devastating. It is a space deliberately excluded from the world we choose to see.

You’ve said that Bloodless began with the desire to “sit beside the woman dying alone in a room.” You searched for the real room in which the murder took place, and when that wasn’t possible, shot in a nearby room with the same layout and function. What was your process for Tearless? What mattered most during research and preparation?

After nearly two years of research, the greatest concern was how to approach the building—both psychologically and physically. The detention center is arguably the visual protagonist of the film, so our approach had to be as careful as if we were working with a human subject.

We debated intensely over how much to preserve or intervene in the space. The structure was in such a dire state—should we document it exactly as it was in 2020, or remove some trash to reveal more of the original form?

Eventually, I decided that anything inherently part of the building—no matter how broken or dirty—would remain untouched. But if an object had clearly been brought in later (by squatters, vandals, etc.), it could be removed. This was not a simple task. As we cleared heaps of rotting trash, we had to simultaneously be careful not to disturb a single glass shard that had fallen from an original windowpane. It was only possible because every member of the art, production, and camera teams fully shared this commitment.

One of the most striking elements in Tearless is the sound of dripping water, of rain—almost like a heartbeat, a metronome of sorrow. The English title, Tearless, is evocative in its irony. Could you speak about your choice of title?

I’ve always been drawn to irony in titles. For instance, the English title of my film 그 집 앞Gue Jip Ap Yi (literally, “In Front of That House”) was Invisible Light; the English title of 두번째 사랑 (DoobeunChea Sarang) was Never Forever. In this trilogy, I also conceived of the English titles before the Korean ones: Bloodless for Dongducheon, and Tearless for Soyosan.

I’m fascinated by bodily fluids that emerge during pain and suffering—specifically blood and tears. Bloodless refers to Yun Geum-Yi, who died from massive blood loss after being struck in the head. Tearless evokes the countless tears shed by the women detained in the Monkey House, expressed in negation—"without tears." The dripping sound you hear in the film serves two purposes: it marks the passage of time, transporting the viewer back to the past when the center was in use, and it signals the ghostly presence of a woman still lingering in the space. Eventually, that faint drip swells into a full downpour—a torrent of rain that engulfs the viewer in the final scene.

I heard that creating the rain effect in a 360-degree VR environment for Tearless was especially challenging. Despite advances in VR technology since you made Bloodless in 2017, what were some of the technical difficulties in Tearless?

Technology has advanced, but the constraints of budget and international coordination made this project no easier. Shooting in live-action VR itself is a challenge, but rendering rain in 3D CGI while maintaining the tactile quality of live-action footage was a monumental task.

We initially reached out to high-profile post-production studios—including The Mill in the UK and Nightlight Lab in the U.S.—to develop the rain effect. While the technical execution was flawless, the emotional resonance was lacking. The rain felt illustrative, not immersive. Disappointed, I returned to Korea for final color grading and had almost given up on the idea.

That’s when Kim Ki-hyun, the lead compositor at Venta VR, who was helping with final adjustments, expressed how regretful he felt that my original vision had to be compromised. On his own initiative, he experimented with an entirely new approach—something that had never been tried before. And it worked. The rain you see in Tearless was created not by massive studios with cutting-edge resources, but by a small Korean team using painstaking labor and deep technical craftsmanship.

Do you find that the role of the director requires different skill sets when making a conventional narrative film versus a VR film?

Absolutely. More than skill sets, I believe it calls for a different philosophical stance—especially in how one positions their work in relation to the viewer. The conventional 2D narrative film is perhaps the most autocratic of art forms. As soon as you frame an image with a rectangular lens, everything outside that frame is excluded. The viewer can only passively observe what the director decides to show—nothing more. With linear editing, the director even preordains what the viewer should see, when they should see it, and what they should feel at any given moment.

But 360-degree VR is a different world entirely. The director cannot dictate what the viewer sees first, or even where they choose to look. VR, in that sense, resembles experimental theater more than cinema: the audience sits in the center while the performers move around them, erupting from all sides. Perhaps that’s why so many conventional filmmakers try VR once and then retreat from it. (Laughs)

Tearless received the Best VR Work award at the 27th Geneva International Film Festival in 2021, following the Best VR Story award for Bloodless at the 74th Venice International Film Festival in 2017. How do these two honors compare in meaning for you?

2017 was often referred to as the "Year One" of VR. The medium was generating worldwide excitement—comparable to the current frenzy around the metaverse. When the Venice Film Festival, one of the “Big Three,” established a dedicated VR competition, it was a bold dismissal of the traditionalists who believed VR belonged only to video games, not cinema. The media, including The New York Times, praised VR’s potential as a new journalistic tool—a medium capable of catalyzing social change.

So when Bloodless received the top prize in Venice and was later selected as the VR Film of the Year by Filmmaker Magazine, I felt a cautious but real hope that VR could indeed become a democratic medium—a potential “empathy machine” capable of fostering deeper understanding and connection.

But today, the trajectory of VR seems to be veering away from that original ideal. Keywords like “empathy” and “social change” no longer dominate discourse around the medium. The pandemic accelerated a shift toward animation, with live-action VR and documentary VR becoming increasingly rare. In this context, I was perhaps even more moved by the recognition Tearless received in Geneva. While I hold deep affection for Venice—especially since Faces of Seoulonce screened alongside Peter Greenaway’s work there, and I served as a competition jury member in 2009—the award in Geneva felt like an acknowledgment of persistence.

In a field now dominated by well-funded video games and flashy animations, Tearless was an outlier—created with restraint, defiance, and conviction. That it was recognized for those very qualities made the honor all the more meaningful.

When Bloodless won the award in Venice, you noted a striking difference in how Korean and foreign audiences responded. Korean viewers often felt deep fear simply from entering the virtual space of Dongducheon, whereas foreign viewers approached it from a more intellectual distance. Both Bloodless and Tearless confront historical traumas specific to Korea. Could this be why representations of U.S. military comfort women remain so rare in cinema? Do you believe their stories should be further brought into public discourse?

Indeed, addressing the lives of U.S. military comfort women—often referred to euphemistically as “camp town women”—is incredibly difficult, precisely because the issue remains unresolved. Though diminished, U.S. military bases still exist in Korea, and the camp towns that surround them remain as remnants of a living history.

The socio-political implications are vast and complex, which perhaps explains why there are so few films dealing with the subject. But regardless of those complexities, I firmly believe that the rights and dignity of these women must be brought into public consciousness. In recent decades, we've seen the emergence of a new class of transnational Koreans—global nomads who studied abroad early, speak multiple languages fluently, and are celebrated as cosmopolitan citizens of the world. They are welcomed in Korea, in the U.S., and beyond.

But on the other end of the spectrum, we have these women—exploited, abandoned, and rendered invisible by both Korea and the United States. Their mixed-race children, too, live with the legacy of erasure. At one time, these women reportedly earned 25% of Korea’s foreign currency income. How can we talk about Korea’s past—or its future—without acknowledging their role in that story? We all owe them a debt.

In a 2009 video interview on People Inside, you said, “I live with a constant awareness of being Asian, Korean, and a woman, and I try to depict that reality with brutal honesty.” Does that still hold true for you today?

Yes, very much so. Over the past 25 years, I’ve worked as both an artist and educator across Korea and the United States, and while many things have changed for the better, it remains undeniably difficult to exist as an Asian woman in a world still largely structured around white male dominance—even now, when we’re already a fifth of the way into the 21st century.

When I taught at Harvard, I was the first—and only—Asian woman to teach in the Department of Visual and Environmental Studies. At UCLA, I remain the first Asian woman to hold a tenured professorship in the Department of Film, Television and Digital Media. Within the film industry, most professional spaces I enter are still overwhelmingly white and male. This may sound like an old tune, but once you step outside of Korea, you’re quickly reminded how much your identity is shaped, judged, or reduced by being Korean, by being a woman, by the color of your skin.

For me, the most urgent task is not just breaking glass ceilings or repeating narratives of victimhood—it’s the capacity to regard oneself with an uncorrupted gaze, to see yourself clearly and without distortion. That’s what I meant when I said I strive to draw brutally honest self-portraits. It’s an act of resistance, but also one of love.

Tearless is scheduled to be exhibited at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul, in 2022. It will be available through mobile augmented reality and a metaverse-based virtual space. As more audiences engage with this work, what impact do you hope it will have? Is there anything viewers should keep in mind when experiencing it?

Over the years, I’ve worked across genres—from commercial narrative films to video essays—and now I’ve begun to explore cutting-edge platforms like virtual reality and the metaverse. But in truth, I still believe deeply in the power of traditional documentary filmmaking. I have immense respect for nonfiction cinema with a strong narrative backbone—for its clarity, its moral force.

That said, in confronting the issue of U.S. military comfort women, I felt a strong desire to bypass intellectual frameworks and speak directly to the body. I didn’t want the audience to engage only through historical knowledge or sociopolitical analysis. I wanted them to feel—to be moved viscerally, through the skin, the ear, the chest. If a viewer truly feels something, then change in awareness will follow naturally. And I believe that changes in individual consciousness are the only path to genuine social transformation.

So, please—don’t come expecting anything. Don’t worry if you know nothing of the history. Just show up, and allow yourself to feel. One practical request, though: because VR unfolds in a 360-degree space, it’s important that you rotate your body while seated in a swivel chair. (Laughs.) That way, you won’t miss anything.

In several interviews, you’ve emphasized the significance of experience in virtual reality. Could you tell us more about the third and final piece in the U.S. military comfort women trilogy that follows Tearless? In a past interview, you also mentioned considering a conventional film on this subject.

The final piece of the trilogy will likely be the most visually driven of the three. At one time, South Korea had 96 U.S. military camp towns, and the combined footprint of these towns and bases covered nearly 17% of the country’s inhabitable land. Logistically, it would be impossible to visit and document all of them in VR, so this third film won’t focus on one specific location like Bloodless or Tearless. Instead, it will adopt a more distilled, symbolic approach.

In parallel, I’ve also begun developing a conventional narrative film on this subject. After completing Tearless, I finally felt a faint sense of readiness—both emotionally and aesthetically—to tackle this history through traditional cinematic means. The film will trace the lives of several women from the early 1970s to 2017, mapping how their experiences inside and outside the camp towns resonate with—and implicate—all of us. It’s a story that reveals how the legacy of U.S. military camp towns is not isolated, but in fact woven into the everyday lives of countless Koreans, whether we acknowledge it or not.

Like most of my previous works, this new film will likely be a Korea-U.S. co-production, developed and shot across both countries.

In an interview over a decade ago, you expressed your artistic dream as: “The most personal story is the most political; the most specific is the most universal. I want to make films like that.” Does this aspiration still hold true today, or has your vision as a director changed over time?

That phrase—“the personal is political”—originated as a feminist rallying cry in the 1960s and ’70s. A decade ago, I think I was still very much driven by that ethos, with a clear desire to create films that embodied that belief. These days, I find myself leaning toward something simpler, though perhaps more challenging: I want to make work that is honest and sincere. Films that resemble a kind of self-portrait.

The characters in my films all feel, in some way, like parts of myself. That’s how I understand the creative process—as something only possible through deep embrace. When I teach, I tell my students that if they can’t answer two urgent questions—"Why me?" and "Why now?"—then they must reexamine the authenticity of their work. I hold myself to the same standard. Those questions are a compass, both artistically and ethically.

You are currently a tenured professor in the Department of Film, Television, and Digital Media at UCLA. You’ve also taught film theory and practice at Harvard University, where you received the Distinguished Teaching Award. In 2018, Variety named you one of the top ten film educators in the world. Outside of your creative work, what draws you to teaching? And, if I may ask, what is your teaching philosophy?

To be honest, I believe arts education is, at its core, a simple calling. It is simply about helping individuals cultivate their inherent uniqueness. Each soul already possesses its own singularity—education’s role is to help students find a form that can best express it, and ultimately, to help them shape a voice that can communicate meaningfully with the world.

Of course, part of that process involves preparing students to engage with the rapidly evolving values and technologies of our time. For instance, one of the courses I taught in 2022 focused on using AR (Augmented Reality) to visualize and translate into art the data and statistics related to anti-Asian hate crimes that surged in the U.S. during the pandemic. The consciousness-raising movements in the U.S.—beginning with #MeToo in 2017 and carried forward by Black Lives Matter—have irreversibly transformed a generation. Many of my students now feel an urgent desire to harness moving images for the purpose of social change. My course Visualizing Anti-Asian Violence was both a response to that desire and an experiment in adopting a lab-based pedagogical model inspired by the sciences—one that emphasizes autonomy and collaborative inquiry.

Today’s students are extraordinarily astute. In an era where nearly anything can be self-taught online, I often feel I have little to offer them in terms of technical or informational knowledge. More often than not, I find myself learning from them, astonished by their brilliance. And yet, I believe there is something only a human teacher—one bound by mortality—can do: to look at a young, unformed artist and see the outline of a future master. To believe in that potential, to nurture it, and to wait patiently. When a mortal teacher waits for another to grow and thrive, that waiting itself becomes a quiet act of giving—of offering one’s own life in the service of another’s becoming.

Tending a garden occupies much of my daily life, alongside filmmaking—and I find teaching remarkably similar. You plant tiny seeds, water them, ensure they receive light, and then you wait. And when the flowers finally bloom, the wonder of that moment makes you forget all the labor and uncertainty. To witness not just the blossoming of an artist’s work, but the unfolding of a human being—that is a rare and humbling privilege. I consider myself incredibly fortunate to be part of that process.